BRAIN WAVES

SEA ISLAND’S MORRIS PICKENS CAN BRING TO YOUR GAME WHAT HE DOES FOR PROS LIKE ZACH JOHNSON

When I was a junior in high school, I was watching a late-night basketball game and they showed John Stockton and Karl Malone in the gym with this guy. They were hanging out talking and shooting free throws. Then they got on this private plane to fly down to play the Lakers. I’m thinking, Are they paying this guy? It turned out that guy was a sports psychologist. It didn’t look much like a job to me; it looked like fun. So I started looking into it.

I went to Clemson and studied psychology. When I finished my undergrad work, there were about four places you could go to grad school that taught applied sports psychology. One of those was Virginia, which is where Bob Rotella was. Since I had played a lot of golf, I thought that would be best. All my classes were about confidence or motivation or youth sports or gender and sports, motor learning, kinesiology, all that kind of background stuff.

When you get out of school, you’re not going to have a lot of clients right away, so you have to basically figure out what you’re going to do while you build your practice up. I was married right out of college and my wife was in pharmaceutical sales, so I said, “I think I can do that while I build up my practice.” So that’s what I did for about eight years, just building up the client base. That was the late 1990s. In 2005, I got the opportunity to move down to Sea Island, and that’s where we’ve been ever since.

If people ask me what I do, I tell them I’m a sports psychologist. Probably 90 percent of my clients are golfers, but I have also worked with some NASCAR drivers, a couple of NFL players, and a Major League pitcher. Right now on tour, I’m working with Zach Johnson, Nick Watney, Michael Thompson, and Scott Jamieson, who primarily plays on the European Tour.

I would ask guys what they mean when they say, “I’m just playing one shot at a time.” Everybody says that. But when I asked them, they couldn’t give me an answer.There are some older players in the game who think the whole aspect of teams supporting professional golfers is laughable—you know, swing coaches and fitness trainers and sport psychologists. But if you’re going to improve, you have to change some things. Not many players worked out much before Tiger; now they all do. It didn’t take too long before these trainers and coaches weren’t somebody you worked with back home. You paid to have them on the road with you. The game is just a lot different than it was. There is kind of a dividing line. Virtually no one in the ’70s had these traveling support people, and almost everybody had them by the 2000s. So the ’80s and ’90s, in that 20-year period, things changed.

My time with players on the PGA Tour is a lot of walking and talking. I’ll travel on Monday and maybe have dinner with somebody. On Tuesday and Wednesday, it’s two or three hours with each guy—basically nine hours of just walking around or organizing practicing for a guy. I’ll be around on Thursday, too, after the tournament starts, but that’s mostly hanging out, observing guys. I want to see how they’re handling adversity or whether they are getting too fast in their routine. If I can get close enough, I’ll also listen in on the communication with their caddie.

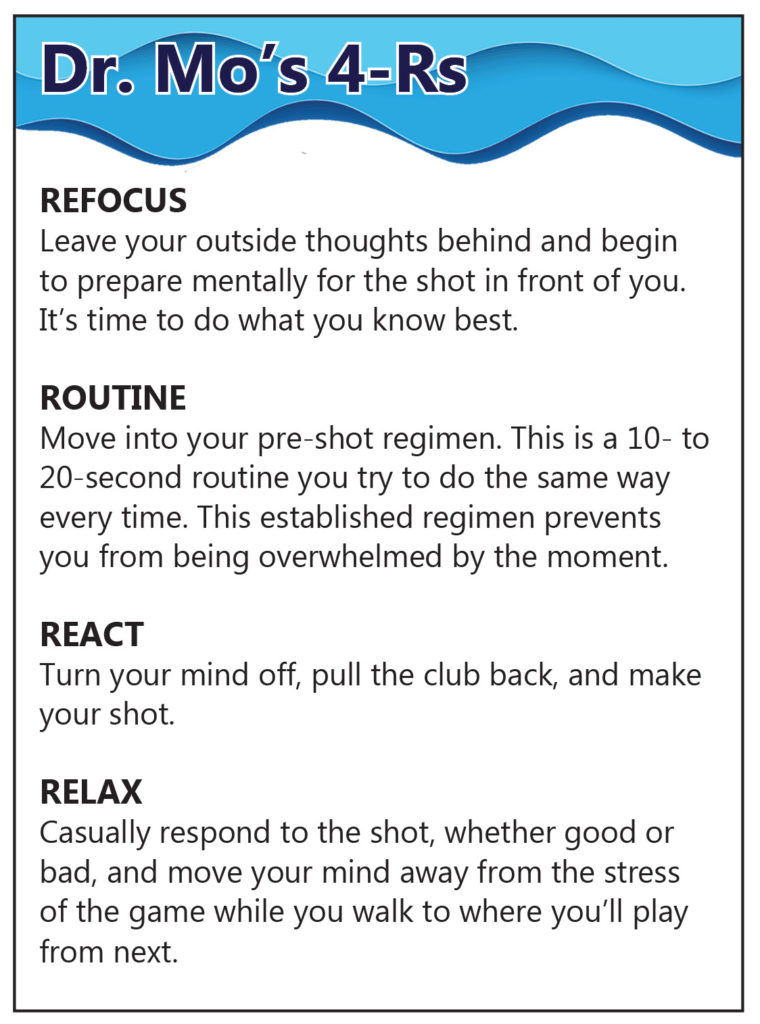

I have four core principles that I use when I talk to players about their game, whether they are a tour player, a college player, or a high-level amateur. These are the 4-R’s: Refocus, Routine, React, and Relax.

Being honest, I came up with this process out of frustration. I would ask guys what they mean when they say, “I’m just playing one shot at a time.” Everybody says that. But when I asked them, they couldn’t give me an answer. They just kept coming up with other clichés: “Stay in the present,” “Play the shot in front of me.” They needed a process, a way to work from the time before the shot, to their pre-shot routine, to their swing. That’s mostly what I do. I help players establish and maintain a routine that gives them the best chance of hitting a good shot.

What sticks with the amateurs I work with is an understanding of what they’re doing around the ball. They don’t really know what their process is. If I can help them really understand decision-making and establish a routine, that sticks. I also find I can help them learn how to practice and learn how to score.

Most people don’t understand shot allocation. I do this thing with all my juniors called “scorecard golf.” This is about how the game is laid out, literally, on the scorecard. Right off the top you have 36 putts, 14 tee balls (not including the par-3s), and four wedges on the par-5s. Twelve greens is about average for players who score in the 70s, so they have to chip six times. If we use those raw numbers, 36+14+4+6, that’s 60 shots and they have only hit five clubs: driver, putter, and three wedges. You might hit your 6-iron three times in a round, but you might hit your putter three times on the first hole. So why would you practice your 6-iron more than your putter? You shouldn’t. So just getting players to understand how the game is made up is really important as it relates to lowering your score.

I know you can be skeptical about all this. In some ways, it sounds like common sense. But when I’m interacting with a tour pro, we’re talking about getting these common sense things into the proper order. If you get the principles or routines out of order, you’re not going to get a good finished product. It’s not rocket science, but where it gets away from common knowledge is in the subtle details. You have to be able to pick up on how a player maybe looks like he does the same thing all the time, but actually when he’s got a putt that’s seven feet for par and he doesn’t want to make bogey, maybe he takes one more look at the cup. It’s not as fluid as before, but ever so slightly. It’s not something the average spectator would ever notice. But that’s why I say, “Greatness is in the details.”

There is a lot of redundancy in what I do. The 4-R’s aren’t inexhaustible, but so much can happen on the golf course that you find yourself returning to the foundations all the time. I’ve worked with Zach Johnson since 2006 and still every off-season, we go back over everything. I’ll ask him, “Hey, tell me about your decision making. What were you thinking about this year? What consistently gave you the most trouble when you played in strong winds?” Things like that. What we’re trying to do is make everything really clean. You know how swing coaches work to get rid of extraneous movements to increase efficiency or to remove compensations you have in your swing? I’m trying to do the same thing when it comes to a player’s thought processes. If your thinking isn’t “clean,” it’s just a matter of time before you make a mess!

There is a lot of redundancy in what I do. The 4-R’s aren’t inexhaustible, but so much can happen on the golf course that you find yourself returning to the foundations all the time. I’ve worked with Zach Johnson since 2006 and still every off-season, we go back over everything. I’ll ask him, “Hey, tell me about your decision making. What were you thinking about this year? What consistently gave you the most trouble when you played in strong winds?” Things like that. What we’re trying to do is make everything really clean. You know how swing coaches work to get rid of extraneous movements to increase efficiency or to remove compensations you have in your swing? I’m trying to do the same thing when it comes to a player’s thought processes. If your thinking isn’t “clean,” it’s just a matter of time before you make a mess!

One place where unnecessary things can get in the way is off the course. So I’m not only working with players in their practice decisions and their playing decisions, but also in their off-course decisions. Are they dehydrated? Are they getting enough sleep? How are they spending the day before a tournament? If we can build good routines off the course, this can have an impact on their game. Of course, it can get bigger than that. Maybe you and your wife are struggling and that’s coming out on the course. I’m not equipped to handle that necessarily, but I can give some basic advice. This is where my faith and the way I live my own life can come into the picture.

I came to Christ through a crisis, if you will. When my daughter was seven, she was having her tonsils taken out. As she was coming out of the procedure, the tube malfunctioned, she developed pulmonary edema, and she ended up in the pediatric ICU for four days. Before this I had been hanging out with some guys who believed in Jesus, but I had been kind of rationalizing everything away and not making a decision about it. During this time when my daughter was hospitalized, one of those guys came up to visit, and we went down to the cafeteria in the hospital in Columbia (SC), and I gave my life to Christ there.

I’m not going to be an evangelist with the players I work with. I’m hired for golf. For any of these guys, though, the relationships develop. They talk to you about golf, and they talk to you about more golf, and they see what you are talking about, and then you just get into normal family discussions. Over time it leads to deeper discussions.

Yes, I spend a lot of time “working on” others, but I know this is important for me, too. I have a Tuesday morning group at my church. It’s a group of guys for Bible study. We pray and share. Then I have a couple guys that I would say are mentors for me. They’re a little bit older; one of them is the family pastor at our church and the other guy used to be an elder. I also have one guy in golf who is a really good teacher and strong in his faith, and we’ll bounce things off each other and just kind of share. My “team” might not be as strictly defined as some of the players I work with—they could tell you exactly who is on their team—but I know the three or four people I’m going to turn to if I’m looking for advice, especially if it’s in the realm of family or faith.

Life is like golf. If you’re in the fairway with an 8-iron in your hand to an accessible hole location, maybe your routine doesn’t matter so much. But if you’re on the 35th hole of the tournament and you need to pull off this shot to a green surrounded by water in order to make the cut, then the routine becomes your security and you’ll say, “I can hit this shot.” Most days, life isn’t that challenging. But you need to be establishing your routines for the day when the pressure comes. Because it will come. It’s not a matter of “if,” it’s a question of “when.” To me, that’s why my faith is so valuable. It gives me a place to go that I trust. It gives me a person to go to who will never steer me wrong. My job is simply to keep that relationship going by returning to him and not drifting away with the cares of the world.

This article originally appeared in the Links Players magazine 2019 annual edition.