Here’s your basic problem: you’re not Arnold Palmer. You’re not Annika Sorenstam or Phil Mickelson or even Ben Crane (which would actually be pretty cool, because you’d be hilarious). Since you’re not, you have to think a bit when someone asks you, “Are you a golfer?”

You are a golfer, of course. You play at least once a week—more when the days are long and the projects wane—and your handicap has been dropping lately. You made not one, but three birdies last time out (we’ll forget the “others”). But you know you’re not a major champion, or the winner of the FedEx St. Jude Classic. OK, yes, you won the second flight in your last club championship, but you’re not kidding anyone. You’re not one of those players, the true champions. It’s all right, though. You came to grips with this long ago. And while you’ll never win a giant cardboard check, you’re confident enough to say, “Yes, I’m a golfer!”

Now let’s ask a different question, one you’ve likely never considered. Are you a theologian?

When it comes to theology, we know there are experts there too. And we form images of those theological stalwarts in the same way we do 19th Century golfers—with beards and pipes and tweeds. Even when theologians jump forward into our time, they come with a vocabulary that includes salvific and premillennial and hortatory—that is, when they’re not speaking Greek, Hebrew, or Latin. Put us in a conversation with one of those folks and we may as well be playing match play against Rory McIlroy.

But does this keep us from being theologians any more than McIlroy and his colleagues keep us from being golfers? Isn’t it true that we too can think about God, even if we don’t know all the big words?

The answer is yes and again it is an answer we should be able to give confidently. For a few minutes, let’s explore how.

All drivers, whether or not they think about it, drive with a philosophy behind their actions.

All drivers, whether or not they think about it, drive with a philosophy behind their actions.

If today I am late for a critical appointment, my driving philosophy may be to get to where I am going as quickly as I possible can, even if have to be rude doing it. So I may exceed the limit, swerve through traffic, run late through “yellow” lights, and tailgate in order to urge slower drivers to get out of my way.

In describing both my motivation and my actions, I have let you in on my philosophy of driving, at least for a day. You might say that a better philosophy, if I have such a critical appointment, is to leave especially early and avoid any chance of being ticketed and missing the appointment altogether. And I would agree that that would be an even better philosophy.

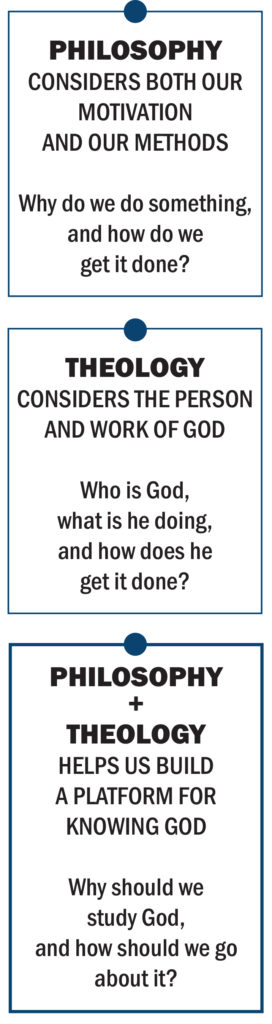

Well, when it comes to theology, we can also begin with a philosophy behind our work. And when we merge the two disciplines, we find ourselves

asking two essential questions: Why should we study God, and how should we go about it? The importance of these questions is akin to a golfer who is trying to get better at the game. This golfer must regularly remind herself why she is practicing and how she is to go about it. Otherwise, her practice risks becoming both uninspired and tedious.

Let’s begin with the singular most important statement we can make in reference to theology, and it has to do with our motivation for engaging in the discipline at all. It is this: The purpose of theological study is to know God. Likely you understand that this is not the motivation of every theologian. Paul warned his readers that while love “builds up,” knowledge “puff s up” (1 Corinthians 1:8). It is certainly possible that humans, driven by intellectual motivation, are interested in one ignoble thing when it comes to the pursuit of theology: they want to show how smart they are (or, at least, they want to show that they are smarter than the other guy).

But if our theology is going to be done for the only reason that counts eternally, it must be done with the ultimate purpose of knowing God. In this way, we

are all theologians the minute we first point our eyes in God’s direction. Even those who eventually turn from God in unbelief are theologians of a sort; they have definite thoughts about who God isn’t in the same way that those who believe have definite thoughts about who he is.

So we can make the effort to know God by way of studying him no matter how new we are to the faith or how sophisticated our thinking is about him. Maybe this is the precise thing the psalmist had in mind when he wrote of God: “Out of the mouths of children and infants you have ordained praise” (Psalm 8:2). Theology belongs to everyone. It belongs especially to those who truly desire to know God.

We should take one step further and note that these steps may be the first steps in a long journey, or the last. If “lifelong learning” is a thing, as they say, then it is a most worthwhile thing when it is pointed in the direction of God. You may just be starting to know God, or you may be wanting to know him yet more than you do now. But if your quest is to know God, you’re on your way to being a theologian, and a good one!

Two passages in Paul’s writing to the early Mediterranean churches give us an impetus for this kind of theology.

In Philippians 3, the apostle established his own thrust of theological thinking: “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of sharing in his suffering, becoming like him in his death” (3:10). We can’t help but notice two things here. First, Paul began by wanting to know. Desire drives many things; if the desire to know God drives our theology, we are well-motivated. Second, Paul had a great purpose behind his desire to know, which was to become like Christ. For Paul, even knowing God was not enough. He wanted to align himself with God, which is a purpose we should pursue ourselves as our theology becomes practical.

Paul’s interest, of course, was never only for himself. He wrote to the churches because he loved them and desired that they too would know God more fully. This was the very thrust of these words to the Ephesians: “I pray that you, being rooted and established in love, may have power, together with all the saints, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge—that you may be filled to the measure of

all the fullness of God” (3:17-19).

Consider two operative expressions here: (1) “Have the power to grasp.” Paul wanted his beloved people to lay firm hold of Christ’s love for them. (2) “That you may be filled to…all the fullness of God.” The end result of understanding Christ’s love was that the people would be filled with God. Good theology takes place not only in the head but in the heart. The knowledge and understanding of God is meant to thoroughly and eternally affect us!

If we are convinced that the work of theology—intention to know God—is for us, then we are led to our second central question: how should we go about studying God? Again, this is like a golfer asking, “I know that I want to get better, but what do I need to do to make this happen?”

If we are convinced that the work of theology—intention to know God—is for us, then we are led to our second central question: how should we go about studying God? Again, this is like a golfer asking, “I know that I want to get better, but what do I need to do to make this happen?”

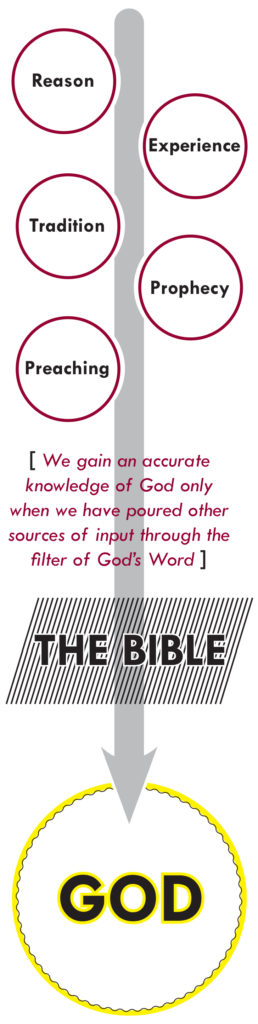

For the follower of Christ, one source reigns for gathering knowledge of God, and this is God’s own Word, the Bible.

Many have proposed the possibility of other God-ordained sources, and we will examine these shortly, but we do well to remember the strong claim on Scripture made by the 18th Century pastor and theologian John Wesley: “Try all things by the written Word, and let all bow down before it. You are in danger every hour if you depart ever so little from Scripture.”

What Wesley undoubtedly meant when he said that “all should bow down before it” was not an idolatrous fixation with Scripture itself. Rather, he was stating that any other source for gathering knowledge about God must be subjugated to the Scripture. This is especially intriguing because Wesley himself suggested that tradition, reason, and experience were legitimate auxiliary sources of knowledge about God. To these, modern day Pentecostal/charismatic thinkers may also add the category known as “prophetic words,” where believers with prophetic gifting receive and deliver words from the Lord, usually specific to individuals or congregations. We also recognize in denominations with strong preaching traditions that the learners are gathering knowledge of God through the words of the preacher.

But in order to trust any of these other sources, we must pour them through the filter of Scripture. Why? Because, as Paul wrote to his protege Timothy, “all

Scripture is God-breathed (God-inspired).” That is, we know precisely where the words of Scripture come from.

And yet, each of these things may be truly helpful as we seek to know God.

Reason. God created a world of order. When we think on the way things work—for instance, the intricate processes of the human body—we may be led to say, “This only makes sense is if there is a master designer behind all this connectedness.” Certainly, if we are to love the Lord with all our mind, God will meet us when our mind is at work.

Experience. The testimonies of men and women as to what God has done in their life allow them to express the very kind of faith Scripture affirms as authentic and saving. Sometimes experiences are dismissed because, as we know, one does not always see clearly in the midst of powerful circumstances. However, we must also recognize that the Bible is in many ways a large collection of people’s experiences with God, and through them we learn much about how God accomplishes his purposes.

Tradition. Here we enter a difficult area because not all matters of theology are clear, even in Scripture. For instance, some denominations adhere to a tradition where they do not allow for instrumental accompaniment of singing. Why? Because the New Testament never indicates that instruments were used in the early church. Other denomination see no biblical injunction against such instrumental support, so they allow for such music. What does such a difference teach us about God? Perhaps not what he prefers in terms of musical worship, but that he allows for some breadth of expression within the universal body of believers.

Prophecy and preaching. We will combine these two here because they are similar in the sense that a spiritually gifted believer, either a prophet or a teacher, stands before the people and helps them recognize the Word of God for their life. We assume that prophets and teachers spend time in prayer and study that many lay people do not, so we are glad for the help in understanding and applying Scripture, especially where it is difficult to understand and where it enables us to know God better.

Yes, there are possible deficiencies in each of these arenas. All of them may miss the mark of Scripture, reminding us that we must go there first and last in our investigation of who God is.

But here is another concern: even with the Bible in hand, we must guard our desire to know God and not be sidelined by self-serving pursuits. In John 5, Jesus confronted the Pharisees about this very problem, telling them, “You diligently search the Scriptures because you think that by them you possess eternal life. These are the Scriptures that testify about me, yet you refuse to come to me to have life.” The grave error of these religious leaders was that they did not find God’s messianic work in Jesus in the Scriptures. They missed the Savior.

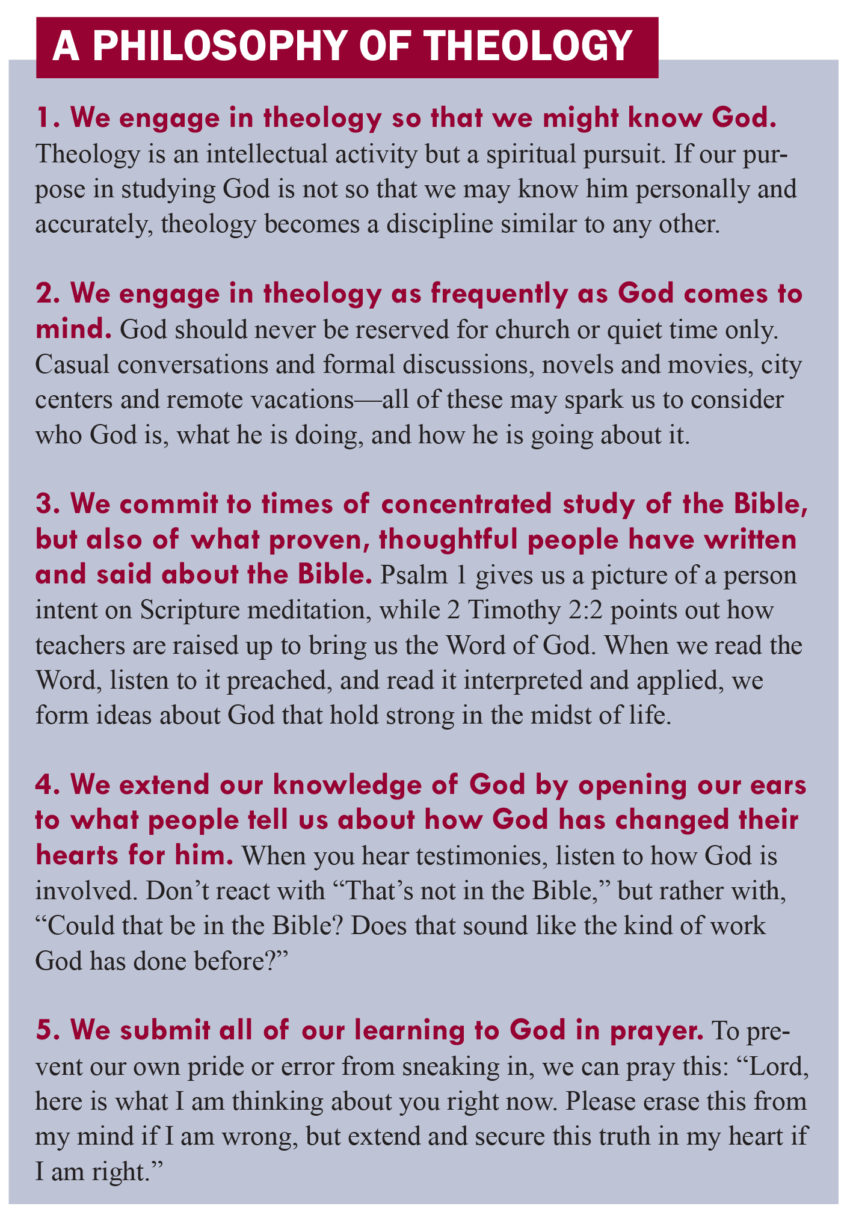

With all this in mind, we can now line out a philosophy of theology, complete with our motivation and our method. Such a list can be more expansive, of course, but for those reading this article, the guide below will allow you to stay focused on key aspects of seeking and knowing God.

In the end, we want any reader—even if you are not a golfer— to be equipped to add to their knowledge of God. You can find ideas about God just about anywhere,

but not all of those ideas are biblically supported or lead to confusion. By keeping your own theological work centered around Scripture and pointed toward knowing God personally, you stand an excellent chance of satisfying Paul’s desire for us all: that “you may grasp how long and wide and high and deep is the love of Christ” for you.